Tomas Petricek, @tomaspetricek

30 August 2017

Six years ago, I started working with Phil Trelford on an

F# course that eventually became FastTrack to F#.

We first ran the course at SkillsMatter in London on October 27-28 in 2011.

To celebrate the anniversary, we partnered with SkillsMatter to offer 25% off the upcoming

course on October 16-17 in London. Just use the F#-OCT2017 code when registering

via the course page at SkillsMatter. However, I also

wanted to use this opportunity to reflect on how our approach to teaching F# has evolved.

The course has always been focused on people who want to gain practical experience so that they can get started with using F# in practice. However, we keep improving and adapting the course almost every time we run it and so the last six years provide an interesting insight into the F# ecosystem, community and also our ideas about best ways of teaching F# and where F# can make the largest difference in practice.

There are a few interesting trends over the last 6 years that are reflected by the course contents:

From functional to functional-first. We started with a lot of emphasis on functional programming concepts. Over time, the F# style evolved to something the community now calls functional-first and so we focus less on some traditional functional concepts and more on mixing them with other important (non-functional) aspects of F# programming.

New cool libraries. There are always some cool new things that appear with a lot of noise (and get their own section in the course) and eventually become yet another, occasionally useful, tool (few slides in other sections). For example, LINQ, Task Parallel Library and Reactive Extensions all still get some space, but much less than when they first appeared.

Microsoft and F# ecosystem. When F# appeared, we focused on using F# with other .NET technologies coming from Microsoft. This is still important as the .NET interoperability gives you access to a large number of fantastic libraries, but the F# ecosystem became a lot richer, and so the course now mentions many libraries that are F#-specific including type providers (F# Data), web servers (Suave) and build system (FAKE).

In the rest of the article, I will write about how the course evolved and look at some of the notable changes (as well as things that have not changed) in more detail.

The course keeps evolving pretty much every time we run it, but I split the history into three major versions. The early days is from around 2011, the second iteration from late 2013 and the modern times from 2016 onwards.

When we started, LINQ was already around for a few years and we saw F# as a natural next step for C# developers who want to apply the power of functional programming to areas beyond just data querying. We used C# to explain a number of functional concepts such as higher-order functions, functional immutable lists, we discussed how functional ideas relate to object-oriented design patterns and we even had a C# monad example.

The focus on functional programming made sense at a time when everyone was excited about LINQ, but it paints an inaccurate image of what programming in F# is often like. For example, function composition is important in theory, but you can write quite a lot of F# code without using it explicitly. So, while the course still uses many functional programming concepts, we now talk about them more in context of typical problems or situations where they are useful.

Another topic that we covered very early was parallel and reactive programming. In theory, a functional program is easy to parallelize and this was a very attractive promise of functional programming. It turns out, the problem is harder in practice, but more importantly, most programs do not really need parallelism of this kind to speed-up computations. We kept and extended what we say about reactive and asynchronous programming, which is important for servers, user interfaces and streaming systems, but we now discuss CPU-intensive parallelism only briefly.

Early days keywords: Functional programming, higher-order functions, LINQ, lists and data structures, recursion, design patterns, F# and C# interoperability, WCF and Silverlight (!)

In our second iteration, we took a lot of inspiration from Don Syme’s talk Succeeding with Functional-first Programming in Industry and focused much more on application areas where F# has been used in the industry. On the technical side, this still means using many functional programming concepts, but we restructured the course to talk more about subjects such as data analytics, domain-specific languages and testing.

The focus on data analytics was partly inspired by the fact that F# type providers just shipped and this inspired quite a lot of new interest in F#. We showed this in larger context by building an ASP.NET MVC application in C# that used an F# data analysis library. I think this is still one of the nice ways of getting started with F# and it also inspired a separate Pluralsight course. We still talk about working with data and analytical components today, but it is not the only focus of the course. Nowadays, we try to give a more representative sample of all the different things that one can do with F#.

The other interesting theme is domain-specific languages (DSLs). When we added it to the course, we spent a lot of time talking about various tricks you can use to make your F# code read nicely, almost like English. While there is a plenty of fun F# features to do this, we realized that the value really comes more from the domain. The core F# language is fantastic at capturing the domain and making the result syntactically nicer is a lot less important. So, while we may still write a custom operator or even a computation builder, we now aim to explain how to use F# to make sense of your domain in the first place.

Second iteration keywords: Analytical components, data science, domain-specific languages, testing, asynchronous programming and agents, ASP.NET MVC

In the current iteration of the course, we aim to combine solid foundations so that attendees learn how to use F# in an idiomatic F# way with a number of practical applications that illustrate the areas where F# excels. However, it differs from the earlier versions in two ways. First, we talk about functional-first programming rather than functional programming and, second, we look at application areas where F# not just works great in theory, but where it is also supported by strong existing ecosystem and community.

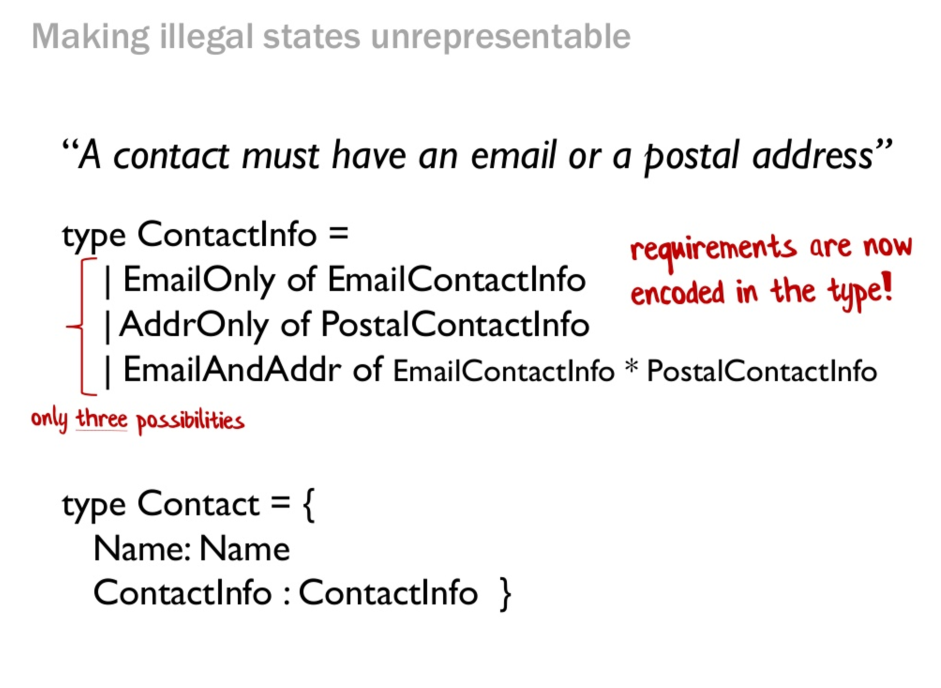

The term functional-first captures the idea that the idiomatic way of using F#, that leads to success, takes many ideas from traditional functional programming, but not all of them. Functional data types, together with pattern matching, are a fantastic tool for modelling and understanding a domain, while functional pipelines are great for sequencing transformations. However, this works fine with imperative and object-oriented libraries and even an occasional mutation at the lower level or object-oriented abstraction at the higher level. In the course, we give attendees enough examples so that they will follow and recognize this style.

When it comes to applied F# projects, we want to focus on areas that work well and have a guarantee of a long term future - this can be thanks to Microsoft support or thanks community commitment. For example, one of our examples now shows the Suave web server, started through the excellent FAKE build system, using Paket for dependency management. This gives you an example of a small, but complete slice of the community-driven F# ecosystem. Of course, we do not focus solely on the community and give space to, e.g., using F# to write a library or a script for a large .NET system.

Modern days keywords: Functional-first, domain modelling, transformations, type providers, asynchronous programming, server-side, infrastructure, F# Software Foundation, Suave

For the next iteration of the course, I will be looking at two improvements. First, I would definitely like to include Fable, an F# to JavaScript compiler with an extremely active community. Fable lets you target the browser and mobile (via React Native), but it also lets us explain elegant functional-first design patterns such as the Elm architecture for building user interfaces, which may be equally useful on the desktop.

Second, I want to finish the transition to functional-first perspective on the F# language basics. I believe I now have a very good intuitive idea of what the right choices are, but I would like to distill this into a more concise guideline. In traditional functional programming, you simply avoid all mutation and the rest (including recursion and even monads) follows. Is there a similar simple principle for functional-first programming? I’m hoping to find out!

We are still teaching F# in the course and the core language features are also still the same, but I think we now also better understand the idiomatic F# style that we now teach more explicitly than we used to. The things that changed include not just the libraries, but also the audience and the ecosystem.

We always want to use some fun, practical examples and so we try to build something practical. The frameworks keep changing. It used to be Silverlight, WPF, Windows Forms and I would like to use Fable next. However, the F# way of interacting with all of these has remained very similar.

The functional-first style means that most of your domain is immutable and you integrate it with some tiny bit of mutation at the top-level. In the course, we also use asynchronous workflows for user interface programming, which means encoding state machines using recursion with an occasional mutation to update the user interface. A variation on this approach works with pretty much all user interface frameworks that we’ve used throughout the years.

When we started the course, our audience was primarily existing .NET and C# developers. This meant that everyone knew how to use .NET libraries and we could use them without too much explaining. We could also explain some ideas in terms of what people knew about object-oriented programming. For example, some people understood F# discriminated unions once we told them they are a bit like class hierarchies.

Nowadays, the audience is becoming a lot more diverse and so we get a mix of C# developers, people

with some background in other functional languages, C++ developers (who like printf!) and also

Excel programmers and others working primarily on mathematical and statistical models. It turns out

that C++ and Excel programmers are pretty good at learning F#, but we had to significantly expand

our set of analogies that help people understand F# features.

As already mentioned, we started with a lot of focus on core functional programming concepts that people learned through LINQ, such as higher-order functions, polymorphism and ways of implementing those in F#.

Over time, our focus shifted to how to use F# to model your problem domain - be it using types (see Scott Wlaschin’s great Domain-Driven Design series), or by composing transformations using the pipe operator.

This is an interesting change, because we technically still talk about the same things. Functional types and higher-order functions are an important component of both. However, the perspective changes quite a bit. I like this trend because focusing on the domain is where F# shines and it also helps you not to get lost in overly complex abstractions.

As I mentioned earlier, we initially focused a lot on how to use F# to write an analytical components. The idea was that you could easily use F# to write a bit of business logic and then integrate it into a larger application that deals with data access and user interfaces. The motivation for this was that using F# with some of the .NET libraries designed primarily for C# (like WPF or ASP.NET) was not always smooth.

Using F# for business logic is still one of the great ways of using it, but the F# ecosystem also got much more mature, which means that there are fantastic F# libraries and tools that let you nicely use F# in other areas. These days, we cover F# type providers and data analytical libraries (F# Data with a few other FsLab bits), building and packaging tools (FAKE and Paket) web libraries (Suave and Fable), as well as testing tools (FsCheck). Those also happen to be the most loved F# libraries according to the annual F# survey we run.

Finally, another thing that has changed (and that caused us some pain in the second iteration) is that the attendees increasingly use F# on Mac and Linux using Visual Studio for Mac (formerly Xamarin Studio), Ionide in VS Code or in Atom or even emacs with the F# mode. We now adapted the course to be fully cross-platform and only use libraries that work equally well on Windows, Mac and Linux. In the early days, this was still hard, but nowadays, pretty much all F# libraries are multi-platform, so this got a lot easier.

We also fully adopted Paket for our sample projects, which solved a lot of pain points with restoring packages and making sure people get the right versions of everything we use. Looking forward, we eventually plan to switch to .NET Core, but there is still quite a lot of work that needs to be done on the F# ecosystem.

It is clear from our experience over the last 6 years that the ecosystem will keep evolving. I expect to add a lot more Fable content, together with Elm-style architecture and React and I also expect .NET Core to play more prominent role on the server-side in the not-so-distant future.

The experience with new libraries and frameworks is perhaps more interesting. I’m sure that new libraries and frameworks for building user-interfaces and web services will appear, but the pragmatic, functional-first F# style is very good at integrating smoothly with different libraries. So, while I expect new libraries, I think the way of using them from F# will remain very much the same. The one nice new thing is the rise of the Elm-style architecture, which can be nicely implemented in functional-first F# style, but is a bit different than what we did before.

Finally, I think that we will keep using the functional features of F# more as means to an end, rather than as the end itself. Domain modelling and domain-driven design capture these ideas quite well, but I would not be surprised if we found even nicer way of talking about the principles behind the functional-first F# style of programming.